Hi. This is what’s left of Daniel Nava.

It was our last day in Asheville, and Aislinn drove us up the Blue Ridge Mountain Trail to watch the sunrise. The pavement was slick and the twisty path was encumbered by a dense brume. I was barely alert, sleep-deprived over the preceding week of booze, food, hiking, and hot tubbin’. Ominous dark tunnels gave profoundly tangible meaning to the phrase “light at the end of the tunnel,” with the encroaching fog threatening to swallow us whole. We reached our vantage point and it was subsumed in a mist. Twenty feet away and Aislinn’s visage would vanish, in a sequence that felt ripped out of a Haruki Murakami novel. We retreated back down the mountain and almost instantly saw the fog lift, providing a stunning panorama of the mountainscape. We pulled over, took our requisite photos, and saw the fog retreat to another part of the planet.

I saw Wayne Coyne perform for the first time since 2007. Back then, I went to the show with Karina. One of the first things we did before dating was exchange CDs, trying to impress one another with our catalog of tastes, as if that matters (it still matters to me). I offered Radiohead’s Hail to the Thief and Arctic Monkey’s debut album. She provided me with Muse’s Absolution and more importantly, The Flaming Lips’ Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robot. Over 15 years later, Coyne performed Yoshimi in full. Inflatable pink robots stood tall as Aislinn and I occupied the front row of the Salt Shed. When they deflated, the coated vinyl fabric would collapse onto us. In the meantime, you could catch a glimpse of Coyne’s infectious smile as he urged everyone to yell as loudly as possible. It’s one of the best shows I’ve seen in my life.

The best piece of media I consumed in 2023 has been Bill Hader’s Barry. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that I could relate to the delusional hopes of a violent murderer attempting to become a “Good Person.” In the first episode of its final season, an incarcerated Barry (Bill Hader) is told the following by a prison guard: “When I was feeling low, my mom used to say that ‘each of us is more than the worst thing we’ve ever done.’ I always liked that. It gave me hope.” This is prompted by Barry verbally lashing out, and the security guard dropping the front and brutally beating Barry. Compassion has its limits and I’ve seen that firsthand. I’ve replayed that sequence in my brain a hundred times and each time it’s like a spiritual tremor.

I won’t say I’ve recovered from self-inflicted ruin. I probably never will. There are good days and bad days. I’ve tumbled down the helix of despair but gradually recovered. It’s not anything in particular; I just can’t remain at the bottom of that darkness, stuck in the proverbial tunnel without reaching out for light. I’m 35 now and I’m the same age that my father was when he had me. I think about this often. Whatever drove me so relentlessly seems to have finally calmed as I sit in a busy cafe on a rainy June morning. “All we have is now” repeats Coyne on the penultimate track of Yoshimi as I consider the fog rising and drifting to some far off place. All we’ve ever had is now; the rain has briefly ceased and the sun’s emerged from behind the clouds.

BlackBerry

(Matt Johnson)

A few months ago, I taught a couple of classes analyzing the poetry of Emily Dickinson through the feminist lens of bell hooks, specifically in relation to her work in All About Love. What it ended up becoming was a discussion on masculine identity, with an emphasis on the following quote from hooks, “masculine identity offered [to] men as the ideal in patriarchal culture is one that requires all males to invent and invest in a false self.”

It’s an applicable quote to what’s going on in Matt Johnson’s excellent biopic on the creation of the BlackBerry. What initially started as a coterie of Canadian nerds happy to eke out a living becomes a fascinated exposé on capitalism run amok. Infinitely more complex and formally rigorous than Ben Affleck’s Air, BlackBerry centers on a lot of the same concerns regarding capitalism’s unceasing demands. Mike Lazaridis and Douglas Fregin (Jay Baruchel and Matt Johnson) lack the business acumen to launch their newly-developed cellphone. That is until they meet Jim Balsillie (an excellent Glenn Howerton, cosplaying as Charles Montgomery Burns), who takes the company to another stratosphere before its eventual decline. It’s rare to suggest that Baruchel is the best aspect of anything but his character here, if not performance, offers a fascinating case-study on how capitalist ideology corrupts our integrity and scars the soul.

I understand why some may argue that all of this is obvious, or simply doesn’t warrant my effusive enthusiasm. But it’s really the killer ending that unites all its various themes, along with Mike Lazaridis’ fascinating character development, from an engineer that values integrity to seeing it diminish and buckle. That integrity only re-emerges in lonely isolation; after having abandoned his best friend and colleague in exchange for the shoddy craftsmanship that he rejected for so long. It’s an ending that conjures the memory of Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg) in The Social Network, left with a laptop to await a response to a Friend Request . We’ve made our bed, invented and invested in a false self, and now we must lie in it.

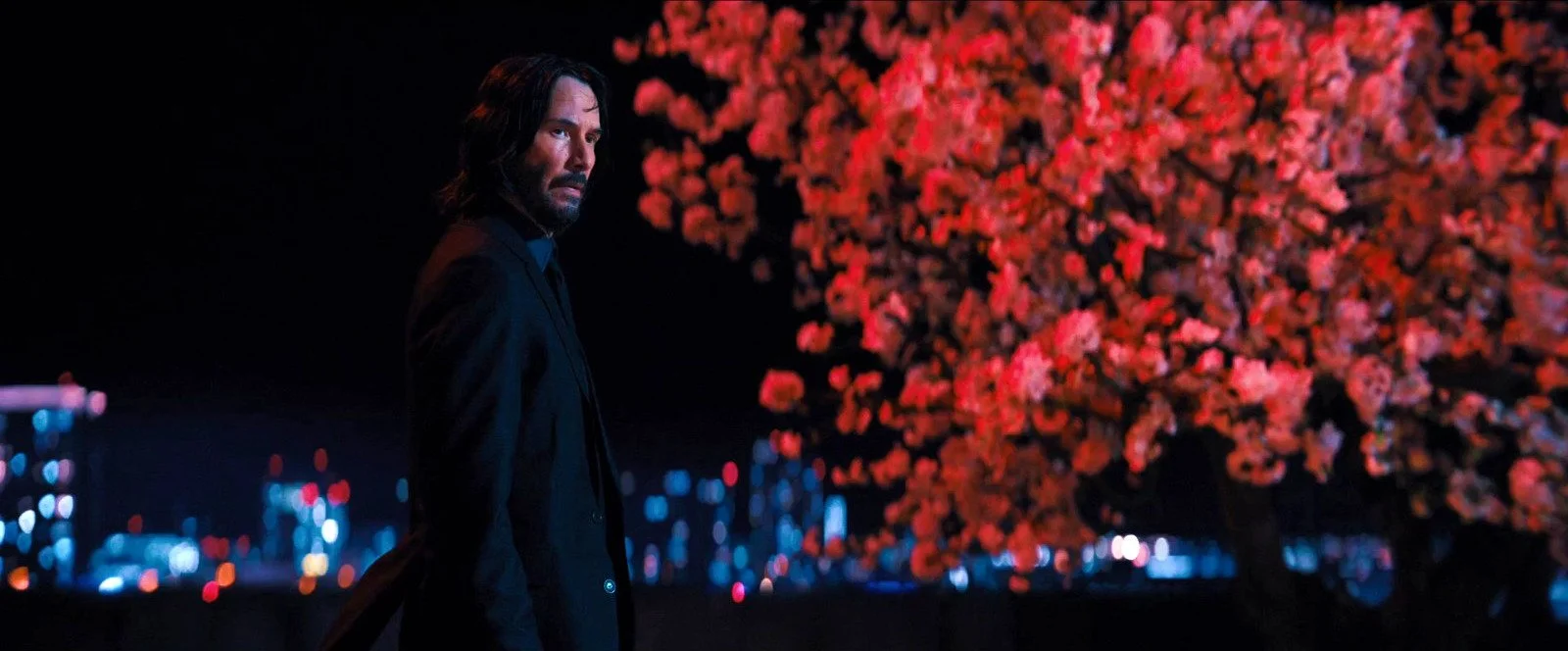

John Wick: Chapter 4

(Chad Stahelski)

The choreography is impeccable. The bisexual lighting is astonishing. Donnie Yen deserves recognition. All these things are true of arguably the best film of 2023 but what this movie means to me is less about its presentation and rather what it’s about. What began as a story of a man transformed by grief becomes an existential epic on transcending nature, on tricky legacies, and the grueling obstacles we must overcome to seek out some measure of personal redemption. John Wick (Keanu Reeves) tumbles down the stairs leading to the Sacré Coeur, only to get back on his feet with the help of a friend. The sequence encapsulates everything about the endurance of the human spirit. Everywhere Wick goes he brings with him darkness in place of light, affliction in the face of health, misfortune when confronted by hope, etc. It’s a feeling I empathize with down to my marrow. The cascading impact of his actions in the first film and the way in which Wick’s world opens up to destroy him are tantamount to a sense memory of my own design. I feel this movie, even as I remain slack-jawed in appreciation of its impossibly fluid action sequences and hyperviolence.

Master Gardener

(Paul Schrader)

I know on an overt level, that the relative calm that I’m experiencing is temporary. Weeks can pass and provide the illusion of permanence but eventually it all comes to a head in one manner of speaking or another. A few months ago, Aislinn and I were at Marz Brewery, enjoying dinner and karaoke before we were accosted by a triad of overgrown children disguised as concerned citizens. Opting not to cause a scene, we walked away from the confrontation. It’s against my nature to walk away. When before I would verbally eviscerate (my mind and body’s way of confronting conflict), this time I couldn’t succumb to compulsion. The incident spurred on a sense of paranoia about merely inhaling and exhaling, which I guess was the intended effect. And then, nothing happened. Nothing kept on happening, until inevitably I concluded that the external reality was not aligning with my internal worldview; not because it was yet to happen but rather because I made a factual error about what the world inherently can be. When you’re overrun by a toxic worldview, the aperture in which you’re viewing the reality seems bleak and uninhabitable.

Paul Schrader’s Master Gardener is about a reformed neo-Nazi. Narvel Roth’s (Joel Edgerton) checkered past has led him into hiding as a horticulturist for a wealthy dowager (Sigourney Weaver). When you have no one to confide in and those closest to you have abandoned you, you’re left creating trenchant bonds. Schrader’s trilogy of films involving complicated men seeking absolution, embarrassingly, speaks to many of my personal experiences. Joining the ranks of Rev. Ernst Toller (Ethan Hawke) and William Tell (Oscar Isaac), Roth commits himself to a craft, careful not to compromise the fragile ecosystem that has permitted him to have a second chance at life. It’s an immediately recognizable situation. One where compassion is measured and comes with a litany of caveats, asterisks, and footnotes. If you deviate or relapse from the reformed path, your mistakes provoke cataclysmic consequences. I get Master Gardener on a spiritual level. It’s familiar in feeling and tone, in its begrudging nihilism and despairing hopefulness. But whereas the preceding films in Schrader’s trilogy have observed his main characters become engulfed in darkness, with one absurdity upon another pushing his characters down an endless slope, I found Roth’s journey toward redemption to be positively affirming. Choices have been made and we all have to live with it. Like Roth, I press on. And the farther I’m pushed, the more the ground beneath my feet comes to resemble a verdant path. Those mistakes of the past are not permanent aspects of my character. I just needed to surround myself with people interested in mutual growth and not whatever cynical, narrow-minded, and self-involved nonsense that the stumbling blocks of my past life embraced.

Past Lives

(Celine Song)

I don’t know where to begin with this one.

I think Celine Song captures a very specific feeling about the connections we have with people; about how some partners pull something ephemeral out of you, to the point that it becomes practically tangible. Watching Past Lives in a crowded theater, I heard the muffled murmurs of recognition. It made me feel a little less alone knowing, feeling, that the people around me recognize the signs of heartache. Nora (Greta Lee) discusses the concept of inyun with her future husband Arthur (John Magaro); the idea that the exchanges and interactions that have made up our lives are the monumental sum total of countless entanglements in previous lives. That we’ve all met before, helped and hurt each other in immeasurable ways. When asked if Nora really believes this, she confesses that she’s just trying to seduce Arthur. Game recognize game.

It was my second date with Sara, a month since our first date at the handjob tree and Humboldt Park. It was a pleasant summer evening, where we met at the rear steps of the Chicago History Museum. It was still the height of COVID but the lakefront path was open again. We got our life updates out of the way and cycled. She had a minor spill as we made the climb on North Avenue. Maybe she was nervous. But she kept up, in what’s probably the one time she was ever keeping up with me and not the other way around. We sat at a table on a grassy knoll as the sun was beginning its descent, listening to her summertime playlist. We made our way back to the northside, where the luminous Chicago skyline complimented her features as we careened through desolate paths; we owned the night. One spot was closed so we went to an Italian restaurant a few storefronts down and ate outdoors, interacting with the handful of characters that would find themselves lost on LaSalle Avenue on a Tuesday night. It was a scene out of a movie. I would hold onto that date for longer than I should have. As addicts do: much of life is chasing that initial high.

What I see in Past Lives is a model of personal integrity. It’s about making the hard choice of not giving in to carnal compulsion. In many ways it reminds me of Wong Kar Wai’s In the Mood for Love, but told in a manner that mirrors my own experiences a bit more vividly. This movie about childhood friends reconnecting, discovering the deep-rooted romanticism of their lives, and choosing not to indulge in their more primal desires is something I probably would’ve been skeptical of years ago. Now? I think it’s an admirable and oft-times painful film. As someone who has given into impulse, many times, I’ve learned that it simply does not end well. Your mind engineers scenarios, in what becomes a series of mental gymnastics of Olympian-caliber, where your sought-after future could conceivably come to fruition. It’s a fool’s game. The rationale being that life’s “what-ifs” cast a tall shadow. I have my answers now and it hasn’t given my life anymore meaning. If I would’ve read Past Lives’ ending as bittersweet before, I see it now as perseverance of the highest order. I’m trying to be a better person. A big part of that is accepting the unknown path, and not residing in the shadows of the past. I look back on that August of 2020 fondly. It’s a sublime memory to have and for the first time ever, I no longer feel angry about it. The sun had to set and with it an era passed.

R.M.N.

(Cristian Mungiu)

If Master Gardener proves anything, it’s that life is more tolerable with a craft. But what if you don’t have one? Where are you to fit in? Cristian Mungiu’s R.M.N. examines a Transylvanian township’s confrontation with obsolescence, whereby the old methods of patriarchy lack practical use in a modern capitalist system. Here, we find men verbally abused, forced to trek to other countries and away from their family in order to make ends meet. The jobs at home pay inadequately, though there’s frustration with the immigrants that do that take those jobs. Hostility is misplaced and we make enemies out of friends, whereby the binaries that have shaped our worldview create false dichotomies. It’s never been us vs. them. It’s a faulty logic prompted by confusion and feelings of worthlessness. That kind of despair is recognizable and in my weaker moments I think it’s easy to fall into pits of frustration and hate. But what Mungiu has argued throughout his filmography, 4 Months, 3 Weeks, 2 Days, Beyond the Hills, Graduation, and now R.M.N. is that hate offers no solace, no warmth. It just burns you up. Or to use Mungiu’s analogy - it’ll eat you alive. Glad I didn’t see any bears in Asheville.

Showing Up

(Kelly Reichardt)

I scrolled through my Spotify and came across a few of my playlists from 2014. I listened to a lot of indie sleaze back then. Barreling down the lakefront path on a warm summer day, each song carried with it a vibrant reminder of what was past. I forgot these songs existed but they were all so strikingly familiar that I could still recite their choruses. Despite the booze & weed and anger & despair & frustration, my hippocampus still has the recall ability to remember the most useless, trivial things. I, indeed, have some good memories associated with my past.

Against my better judgment, I’ll talk about Yvonne. The first time I saw Kelly Reichardt’s Showing Up, I remarked how it felt like the filmmaker’s first horror film. The lived-in, authentic nature of the film’s art school milieu felt a little too real. The characters reminded me of the intimidating, self-important types I’d see at Cafe Mustache’s karaoke. But as the film progressed in Reichardt’s usual laid-back way, it reveals itself to be a very moving picture on art and process. I vividly remember visits to Yvonne’s SAIC studio, where she’d show me her self-made contraption for producing fiber art. It was a foreign world to me, where we’d rummage through thrift shops picking out material for her to use on reconstructing memes as wall art. I remember, as we were approaching the precipice of COVID as a global event, we went to The Native for a bev. She had always been fairly guarded about her art and for the first time we talked about it in broader, more existential terms. I don’t want this to come across as congratulatory or immodest but I like to think I supported her ambitions in a positive way, particularly in a moment when doubt was settling in. Maybe I didn’t. All I do know was that I admired what she did, genuinely, and that it pained me to see her miss out on all the things that COVID would take away from her. Michelle Williams’ character in Showing Up has that kind of familiar moment, where the cumulative weight of completing a piece, showcasing it to the public, and all the extraneous bullshit of day-in-day-out living rattles her constitution. But the film ends with a note of acceptance. The binaries of victory and defeat seem less urgent. Instead, as Reichardt puts it, it’s just about doing the work and being there. In equal measures I learned what I wanted and what I didn’t want when I was with Yvonne, and for what it was, I’m grateful.

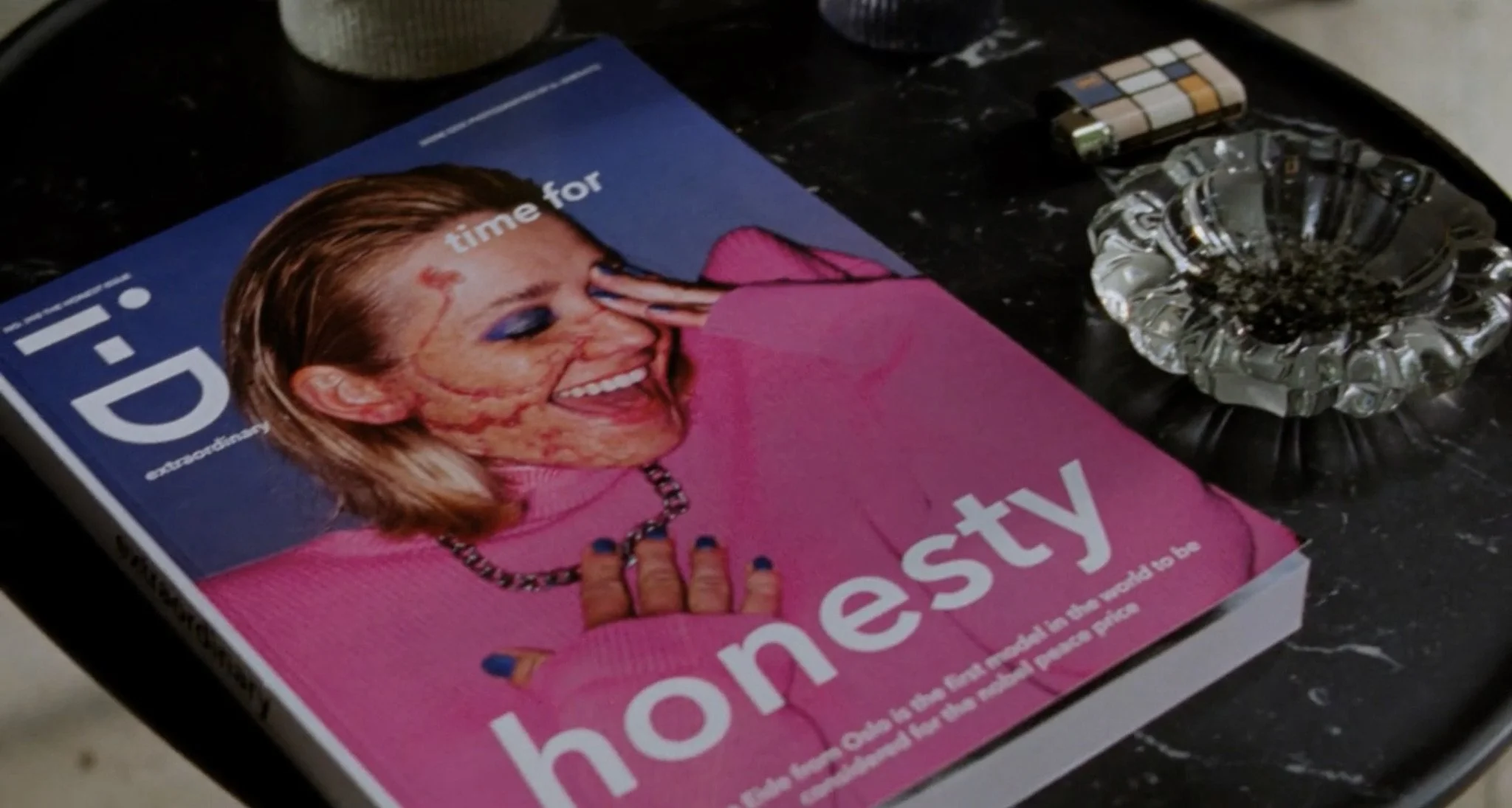

Sick of Myself

(Kristoffer Borgli)

We got a dog. A six-year-old black-and-white blue heeler that meets the conventional qualifications of a gremlin. She’s the worst, but I love her. She does this awful thing where she’ll eat anything. For a while it was my socks, but she’s not above a reasonably-sized wool dryer ball. On our walks, she has a penchant for premium-grade dirt clods of the high phosphate variety that I’m always too slow to intercept so I have to crank open her mouth with both of my hands and use gravity (along with mentally praying to JC, Allah or whatever spiritual-type thing I don’t worship) to jostle it out of her maw. The things we do for those we love and the orifices we plunge wrist-deep into to avoid a vet (or hospital) bill. Sometimes I think of the act as her conscience (the Jiminy Cricket variety), where to ensure her survival I have to intercede. And then I imagine someone pulling the strings in this simulation, and question if I’m completely untethered; a perennial stray designed to make bad decisions and eat shit along the way.

I think about Paul Veroheven’s Total Recall often. Fundamentally, the movie treats dreams and reality as equally awful - but in one you’re important. Which one depends on your temperament. It’s an ideology that can be applied to Kristoffer Borgli’s Sick of Myself. Here’s a film about a young woman that feels nothing until she does. When Signe (Kristine Kujath Thorp) becomes the subject of pity and adoration, she chases after the high. The game escalates until she ODs on an experimental pharmaceutical that leaves her disfigured enough to become a public figure. Again it’s all about angling for adoration, about a glimpse of celebrity, or in therapy-speak, about being seen. What we get is an examination on our diet of delusions and what happens when our dopamine-depleted brains need more to get off. All of this sounds vaguely familiar.

I’m (disappointingly) brought back to (what I thought) would be the last conversation that I’d have with Sara. Following a vapid conversation on perception and forgiveness, linked together by tenuous associations, I was ultimately left to make a concrete choice on what I was going to do with the rest of my life. And like with so much of life, the things you plan rarely turn out the way you want them to. And that’s ok; thankfully, I’ve shed the exhausting narratives that have gone into defending my position, my fucking life, in the world and instead found serenity over the things that I cannot change. Louise Bourgeois advocated to “tell your own story, and you will be interesting.” While the tweedledees of my life may believe in that, I’ve found that telling and retelling this story is only interesting to the speaker. And I’m so very tired of it. “The tide is beyond our approval or disapproval, our acceptance or denial.” “You are what you do, and a man is defined by his actions and not his memory.” I love my banal platitudes.

I need a breath of fresh air but I won’t find one. Chicago is overcome in a smoky haze, a brume that threatens to swallow us whole, filling our lungs and bloodstream with pollutant particles. But the dog is ready for her walk. Shit happens.