The year began in Oʻahu.

There was some initial baggage in coming here, a feeling that I was letting down a past self. I mentally conceived that this was a place intended for me and someone else, but that thought was rooted in an era that has long passed. With Aislinn, hand-in-hand, we were going to traverse the islands and carve our own path. Our first full day was overcast, with plans of parasailing dashed. We made the best of it, carrying on with our newfound passion for waterfalls (a product of our Pacific Northwest trip) by hiking the Mānoa Falls Trail. We donned our hiking boots and rain jackets as a drizzle crept in. We rented a tiny Smart Car and made our way to the trail, feeling every conceivable gust of wind and bump along the road from the presumably shock-less automobile. Beginning the trail, couples and families with their eyes on the exit remarked that we came prepared. The warm air made the trek a pleasant one, but the rain gradually shifted from a steady pitter-patter to a biblical torrent.

I was reminded of my childhood, where on a summer afternoon I was caught in the rain while riding my garish blue-and-yellow Huffy mountain bike. The rain lasted no longer than a few minutes but the downpour left me completely drenched. My mouth agape, my hands ungripped the handlebars as I opened my arms and let out a primal scream (or as close to primal as an eleven-year-old boy that hadn’t hit puberty can get) as I careened through the arteries that made up the Old Irving Park neighborhood. I recall coming home sopping wet, my mother aghast, and never feeling so happy, so alive.

We remained unfazed. My confidence grew with each stride, yet as the elevation increased, the muddy trails began to resemble a mudslide. We pressed on. We passed a handful of like-minded souls who could not have picked a better place to be than here. Our jackets began to wet out, where the fluoropolymer lining could no longer withstand the downpour. We took refuge in what appeared to be a metal cargo container before continuing on. I would catch a glimpse of the waterfall through my rain-obstructed glasses. Call it a baptism. Call it fate, but all of my reservations of the trip were washed away in that instant, all my anxieties of eventually proposing to Aislinn effectively scrubbed from my spirit. A piece of my molecular makeup is part of that trail now, and I look back on that moment with great fondness.

The movies have never meant less to me. Not to say that I haven’t watched anything new or interesting over the last six months, but I’ve become increasingly discerning about my media intake over the last few years. Instead I find myself looking inward by going outward, examining the world around me, cycling more than I ever have, and attempting to make it to all fifty states before the age of forty. The movies I play in my head are the collections of memories of my recent escapes, from tiki drinks in Cambridge, the luminescence of the Coolidge Corner Theater marquee, the sea lion resting her head atop mine in Mystic, the pine scent of the massive cabin near Sebago Lake, or simply burning off some calories after downing a lobster roll in Portland, Maine. And there’s always biking in Milwaukee, where the verdant Oak Leaf Trail lures you in one moment with its all-encompassing white, red, and bur oaks before unleashing the brimming sun right above your head. It’s a summer tradition at this point and to have my brother join me on these cycling journeys has made a world of difference.

Writing less, I’ve found myself yearning for space to read more, picking novels from my bookshelf that I was too weary or intimidated by to commit to. Fyodor Dostoevsky’s White Nights and Crime and Punishment have reshaped my perspective, forcing me to relitigate my past in new ways. My life sentence may very well be to replay the same handful of events in my head, but time is on my side, and with time the painful gulf between what is and what was blurs. Like my namesake, I’ve been thrown into a pit full of hungry lions and survived. All of this - the life I have now - is borrowed time, literally, and I’m certainly making the most of it. I know it all sounds woefully granola and new age-y. I can’t pretend like it doesn’t. Maybe it’s just the perspective of someone who’s lost a lot and needs to make sense of a new world that’s in front of them.

The five films that follow are my favorites in a year of repose and reflection. To even be afforded the luxury of repose is a gift that is not lost on me. And if these acts of reflection are to be seen as hubiristic then.. Well, go fuck yourself because I don’t care. Rather than looming in the shadows as a collection of zeroes and ones, maybe consider the audacity of simply reaching out. I know: rich coming from me. But if you’re reading this you’re reading this for a reason. And whether you care to admit or not: only you know why.

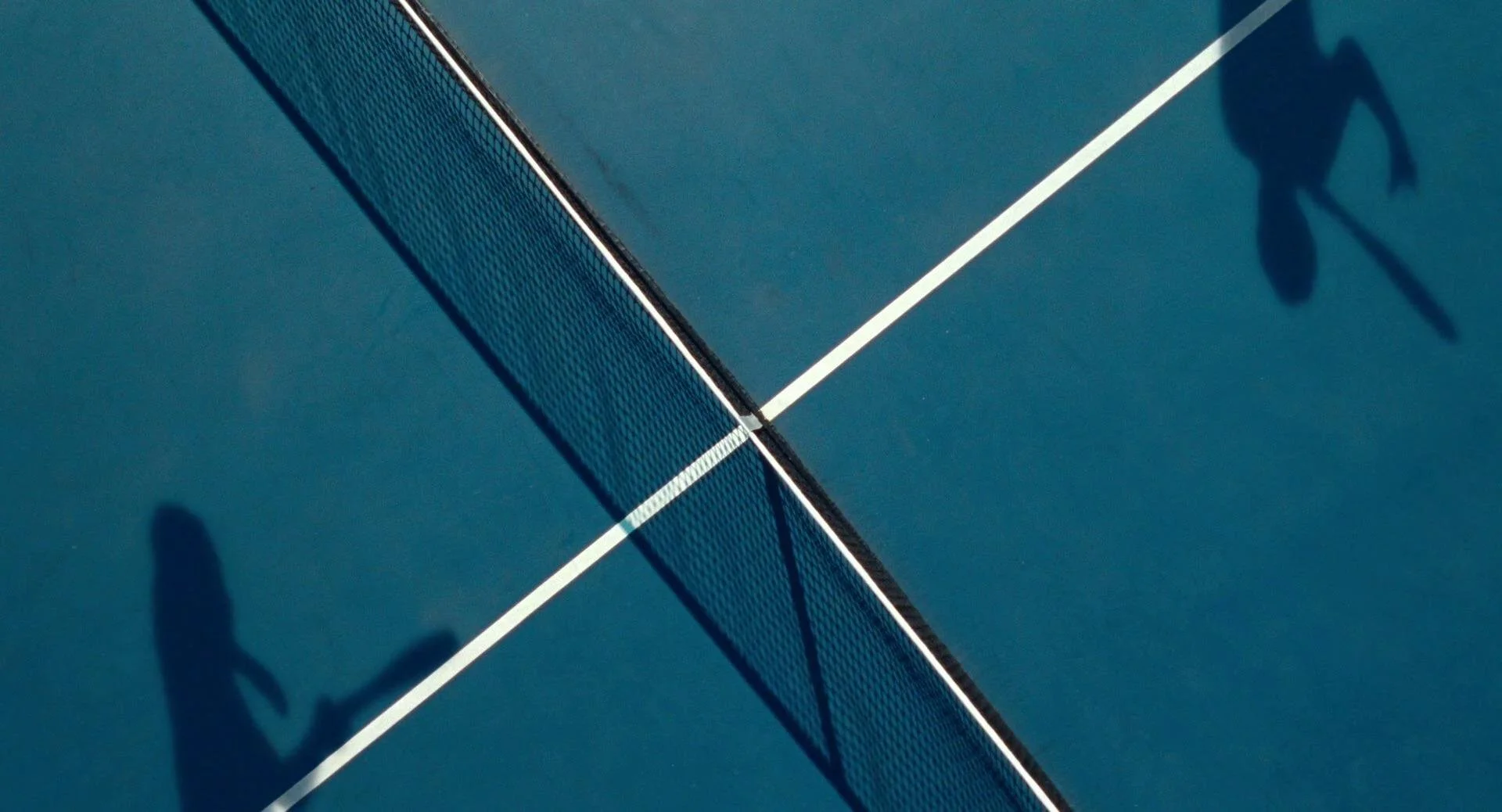

Challengers

Directed by Luca Guadagnino

I lived this! Well, not really but at times I experienced a wicked case of déjà vu watching Challengers, only to be jarred back in place when the ad-lib returned to the tennis court. But Luca Guadagnino’s new film conjured up a lot of memories of past lovers and misplaced passions. Usually, when that’s the case, I’m left feeling morose and despondent, reminded of my personal failures, but in Challengers’ case I was utterly enthralled; captivated by the formal sleight of hand and the kinetic sensuality/sexuality of what was happening on-screen. While a mostly sexless film, what Guadagnino, Zendaya, Mike Faist, and especially Josh O’Connor accomplish, alongside the scripting of Justin Kuritzkes, is a percussive and elaborate exercise in the blending of personal and professional pursuits, where the insatiable drive to want it all means knowing that we may get everything we’ve ever wanted, but accepting that it may not happen all at once, and certainly never like how we envisioned.

Like with anything about tennis, I can’t help but think of David Foster Wallace and Infinite Jest’s Hal Incandenza. The three leads all possess a kind of spiritual link to Hal and his time at the Enfield Tennis Academy, with the prevailing sentiment being that a competitive drive offers these people their only escape from monotony. It’s an act of self-deception, where we analyze three people in conflict with themselves: Tashi (Zendaya) has the mind for tennis but her body fails her, Patrick (O’Connor) has the physicality but not the mind for the game, crumpling when competition gets too fierce, and similarly Art (Faist) can go on the court, but needs Tashi to get him the right headspace. Yet only Art, the most Hal of the three, seems keenly aware of his spiritual cul-de-sac in the game, where his competitive ego finds a worthy opponent in himself. As Art contends with having to play menial games to enhance his waning reputation, I couldn’t help but think of Hal, reflecting on how "he’d been raised in an environment that valued and nurtured his competitiveness and intelligence, but this same environment often left him feeling isolated and disconnected."

Art may be the most emotionally aware of the three characters here, but my kinship remains with Patrick, who can’t help but cling onto hope, in part because tennis is the only thing that has given his life meaning. To transition out of that, to refuse a lifeline, is, from my experience, painfully difficult (if not evidenced by my continuing to write). He’s a perennial fuckup that had to be confronted with everything before eventually coming to terms with his own failures. Or as Hal’s brother, Mario puts it: “[Mario] felt like he’d spent his whole life inside his brother Hal’s shadow, at the Enfield Tennis Academy, a place where the quest for greatness often seemed to take precedence over the search for personal meaning.” What Challengers ends up becoming is a film not about reliving the travails of the past, but instead about the fortitude it takes to meet the rigorous demands of our lives, and to finally come to terms with your identity and ultimately, your place in the world. It’s about how the past intertwines with the present, and how to untangle oneself from its stranglehold. So yeah, I guess you can say I lived this.

La Chimera

Directed by Alice Rohrwacher

There’s the image of a fire-breathing lion, with the head of a goat on the other end and a tail that ends in a snake head. In medicine, there’s the idea of an organ transplant, where the genetic makeup of another combines with yours. It’s a miracle when the two coalesce, but a nightmare when they don’t. Unfortunately, I’m prone to literary flights of fantasy when attempting to discern meaning in my life’s foibles, so I think of a chimera as an unattainable dream, something so far-fetched yet precise, like following a strand from your past in an attempt to remedy the mistakes of the present.

Alice Rohrwacher’s La Chimera believes in that concept too. The film possesses the DNA of her forefathers, from Vittorio De Sica’s neorealism to the present tense familial concerns of Pietro Germi to the broadly existential of Federico Fellini’s oeuvre. What I see in La Chimera is an excavation of the past, an embrace of the warm humanity of the present, and a reckoning of the unknowable future. The throughline of this wonderful film, which details an ex-con’s divine ability to locate buried artifacts and tombs of a Etruscan civilization, is that his great power provides him no peace as he’s burdened by the image of a woman of his dreams. He goes underground, digging up treasures with his goofy tomb raider friends, in search of something more meaningful about himself. And he always comes up missing something, straining to follow a red thread that belonged to his past love.

The ex-con is played by Josh O'Connor, who in the aforementioned Challengers, has emerged as a patron saint to a specific kind of wounded, dare I say toxic, masculinity. In his two roles he’s embodied a lot of my experiences, malaise, and melancholy of the last few years. As Arthur, he finds a home in a place that still treats him like an outsider, possessing no particular desire to utilize his skill-set beyond making those around him happy. But he’s deeply wounded, fixated on what was lost. What Rohrwacher and O’Connor end up communicating in La Chimera is akin to what Sonja discusses with Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment upon hearing the news of his transgressions: “accept suffering and redeem yourself by it.”

I’ve long considered that my mistakes of the past were fixable. I’ve long yearned for punishment, of being incarcerated, as a means of conveying to people that I’ve done my time, and paid my debt. It’s as if it’s something I can point to, a trial where all sides air out their grievances and a sentence is levied. But that’s too easy. With time and reflection I’ve come to the realization that these hopes were rooted in ending my own personal suffering, without taking into account others. It’s my personal battle to wake up to, day-in and day-out. The throughline of that red thread eventually leads Arthur to some modicum of redemption, and I can only hope it will do the same for me. I think I’m getting there, sincerely. And that thought scares me too. Maybe that’s just life; my chimera.

Evil Does Not Exist

Directed by Ryusuke Hamaguchi

For the past year, I've been living in a town

That gets a lot of tourists in the summer months

They come and they stay for a couple days

But hey, I'm living here every day

I don't need the complications, I'm just in it for the beating

It's almost a point of pride, they say that it doesn't happen that often

The evil of Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s new film is not the slow camera dolly that captures tree branches of Mizubiki Village ornating the cloudless, muted sky. Nor is it the percussive sense of dread that Hamaguchi is capable of gradually mounting through extended tracking shots or subtle shifts in perspective. No, if there’s any evil to speak of in Hamaguchi’s new film, it’s the kind of evil that involves businessmen in Zoom meetings, as they fecklessly dictate how their capitalist ambitions will trickle down and benefit everyone. It’s the kind of evil shrouded in HR pleasantries, utilizing the language of the proletariat, adopting whatever slogan-of-the-week to instill a sense of togetherness. It’s an evil of phoniness and inauthenticity, of sincerity with a motive.

Evil Does Not Exist centers on Takumi (Hitoshi Omika), the local handyman of a small mountain village, and his adolescent daughter, Hana (Ryo Nishikawa). Hamaguchi captures the rhythms of this family and the small community they inhabit deliberately, with not a single motion wasted in conveying how these self-reliant, self-sufficient people find their way of life disrupted when news of a glamping site is set to begin development. The Tokyo-based “glamorous camping” company hires actors to run a community forum, where townspeople gather to discuss the basic logistics of such a camping site on their land. The questions are informed and practical - how’s the layout going to be utilized, the size of the septic tank expected to take up their land, the environmental concerns of such a project. The answers to these questions are, in a word, insufficient. What follows in an attempt at offering an olive branch between locals and tourists, and the nightmare that ensues when oppressors are vigilant about remaining outside of the frames of their money-making schemes.

Hamaguchi tells this story of bureaucratic redundancies like a horror film. Through his methodical, unfussy approach he welcomes you into the lull of day-in-day-out routine before seeing it disrupted. In that disruption, we find a kind of horror that’s all too real and familiar. Whatever clinical diagnosis gets levied against me, whether it be depression or adjustment disorder, all I know is that I’ve experienced a lot of dramatic change in my life over the last five years. The life I once knew is completely different now, and for the most part, particularly over the last year, I’m actually grateful for it. But I saw the tides changing in real time, the ravine of my past polluted and co-opted. Much of it was my own doing, my own ineffectuality. But since then, I’ve charted new terrain, and with it, my fences are up, and I’m ready to defend it with all I’ve got. Unlike Takumi, I’m not soliciting new developments or wastes of space or time. I’ve aged a couple decades within the last five years and with it, the borrowed time I’m on is made all the more precious; a resource that I no longer can afford to waste on self-serving arbiters of faux-sincerity. Y’all know who you are. I imagine Takumi knew too.

Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga

Directed by George Miller

I’ve thought a lot about the immutable truth that Dementus (Chris Hemsworth) offers Furiosa (Anya Taylor-Joy) at the end of George Miller’s new film. Furiosa, now having Dementus exactly where she wants him, on his knees with a pistol pointed at him, demands having her childhood and mother back. She wants Dementus to suffer for all the cruelty he’s inflicted, not just on her but on everyone and everything he’s touched. He offers Furiosa some suggestions to amplify his agony, citing that having his back turned to her would permit for more tension, more unknowability, and in it: more suffering. Or as he says: “Minor torture, but any little bit counts.” But the Capital T Truth remains all the same: nothing will remedy Furiosa’s past. You can never balance the scales of suffering.

In my weaker moments, I would reply that it doesn’t hurt to try! The desire for retaliation can often cloud my judgment. And like Furiosa (and several women of my past life), revenge can be a great motivator. The mantra of the past few years have been about hate, and how it doesn’t keep me warm but just burns me up. Yet sometimes I think I’ll set myself ablaze to take those that hurt me down with me. It’s kind of like that David Foster Wallace quote about suicide, as he imagines a burning high-rise where onlookers tell victims not to jump, only to be overwhelmed by the encroaching flames, leading to either self-defenestration or being consumed by fire. Those on the outside don’t really understand what’s happening inside, or what could lead someone to make that leap. When my anger or sadness prove to be too overwhelming, these possibilities - a death in flames or leaping under my own volition - are not as reprehensible as when I’m clear in thought. I’ve gotten a lot better about identifying when I’m in that place and realizing its ephemerality.

Maybe part of the hurt in Furiosa is that Dementus didn’t initially recognize her or remember murdering her mother. But Furiosa reminds him and in that recognition he sees a mirror of himself. Two sides of the same coin, intent on ruling over the Wasteland through vengeance and violence. Furiosa contends that the two are not the same, but I think he has a point. The cyclical nature of violence inspires something of a trickle down effect, resulting in generations of hate. Deprived of anything resembling a home or family, it’s hard not to feel dead. I know I felt that way, as if there’s no reprieve and I’m fated for permanent despondency, roaming the scorched Earth of my past. But then something emerged through the ruin. And through the extinction of my past came a present and future worth living. A present and future determined to not recycle the same strains of hate that got me where I was in the first place. It ends with me.

Hit Man

Directed by Richard Linklater

A former friend of mine would frequently remark on how Richard Linklater was an “idea man.” I can see why he’d say that, and reflecting on Linklater’s filmography, his films have never really struck me for their formal or visual acuity. He’s a perfectly serviceable craftsman, inoffensive though not especially impressive. But when it comes to the ideas he expresses in his scripts, and the actors that communicate them: I’m often bowled over. The Before Trilogy, Boyhood, Dazed and Confused, and several others have all made indelible impressions on me, for better or worse. His new film, Hit Man, is one of his better ones. On first glance, it’s a breezy, if not slight, neo-noir dramedy set in New Orleans starring Glen Powell. Basically, an updated, bayou edition of Out of Sight. But upon further reflection, the film inspires a lot of thought on the nature of performance, the fluidity of authenticity, how we struggle to find ourselves interesting, and how easily tangled we become when we’re infatuated. At its roots, Hit Man is about the lies we tell, and why we tell them. Like always, it’s no surprise that I saw a lot of myself here.

A college professor by day, Gary (Glen Powell) moonlights for the NOLA police. When an undercover cop is on leave, Gary is expected to take his spot, placed into the role of a contract killer for a sting operation. He ends up giving a rather convincing performance, and takes his new job seriously, becoming something of a method actor. As Ron, Gary entraps would-be marks that hope to enlist him for his services. The ethics of this, compounded with the inherently dubious nature of the police, is glossed over. Nevertheless, it’s an important (if not intentional) aspect to the whole picture, particularly when Ron decides to talk Maddy (Adria Arjona), a woman interested in hiring Ron to murder her ex, out of her crime. Why’d he do it? He doesn’t confess it but it’s undoubtedly because of his attraction to her.

Ron is everything Gary wants to be. He’s confident. He’s cool. Ron is the Superman to Gary’s Clark Kent; remove the mawkish glasses and academia and Ron is a superhero. And it’s not just that this new persona is violent in nature, it’s that he’s able to modulate that violence. Maddy finds this irresistible, and the two end up developing a courtship, guided by the maxims they establish, with the obvious intention (to everyone but themselves) of eventually breaking their own rules. The chemistry between these two rivals that of Clooney and Lopez in the aforementioned Out of Sight, and Linklater (along with Powell, who co-wrote the script) stages scenes between the two as if they’re attempting to best one another. This ends up saying more about me than anything else, but all of this makes for an incredibly sexy film. Why, though? These characters root themselves deeply in their lies, yet begin to feel real feelings, and circumnavigate those feelings to keep the charade going. There’s no truth-telling beyond what they’re feeling. I guess what I find so alluring about this, like Jesse and Celine in the Before series, is that through the lies, it’s their feelings for one another that prevailed.

I’ve been in more relationships than I care to remember and each one has ended in their own specific, painful way. Lies were told in all of them, on both sides. But what films like this explore, is that it takes something truly special to emerge out of the wreckage. At Hit Man’s end, I was reminded of a Linklater quote, “memory is a wonderful thing if you don’t have to worry about the past.” True, but maybe - and this is me at my most sanguine - that horrible past can inform a present that’s worth living. If you told me that four years ago, I would not have believed you.

I escaped a snowstorm in Chicago for Miami Beach, caught the sunrise with my brother in Lauderdale-by-the-Sea, imbibed on Angel’s Envy with Aislinn in Louisville, had some vampires flash me in New Orleans, saw the Painted Rocks of the Upper Peninsula while shivering in June, had a coterie of Portuguese nurses stitch me up in Lisbon, witnessed some beautiful vistas at Shenandoah National Park on our way from Virginia to DC, smelled the roses in San Jose while playing tag with my future nieces, willfully succumbed to my loneliness during a heatwave in Philly, blinked while in Denver, gave myself to the Blue Ridge Mountains, climbed vertically in my return to the Pacific Northwest, traversed through New England at a rapid clip, and stripped down to my bare ass with Aislinn at Kehena Black Sand Beach to enjoy our last day in Hawaii, and my first day as her fiancé. I can indeed have it all, just maybe not all at the same time. Life’s downpours can be endured somberly, or with unmitigated joy, but they never last a lifetime. Which, in itself, is a lesson of a lifetime.